[Background Music]

Dr. Michael Iadarola: A vanilloid is—one of the primary vanilloids that almost everybody's familiar with is capsaicin. So that's the active ingredient in hot chili peppers. And in the 90s and 80s, people were very interested in identifying the receptor.

[Background Music]

Dr. Ellen Staedtler: We also know from clinical experience if we apply an opioid intrathecally—so in the spinal base—that also acts really, is really efficacious to eliminate pain from tissue damage, for example.

[Background Music]

Intro: From the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, this is Discovering Hope and Science.

Sean Markey: I'm your host, Sean Markey. Today's episode, we speak with two researchers from the NIH Clinical Center Department of Perioperative Medicine. Dr. Michael Iadarola is a pharmacologist and senior research scientist who studies the neurobiology of pain and pain control. And Dr. Ellen Stettler is a physician scientist, anesthesiologist and clinical fellow who uses the methods of molecular biology to study somatosensory neurons in skin and deep tissue. Their mission is to understand the fundamental physiology of pain and to use that insight to develop new avenues to treat pain. Drs. Iadarola and Staedtler, welcome to the program.

Iadarola: Thank you very much.

Staedtler: Thank you. Happy to be here.

Markey: You collaborated on a study, recently published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, that investigated pain-sensing neurons in humans. What did you learn?

Iadarola: We know that there's a very important population of pain-sensing neurons in the sensory ganglion. These are collections of cells that fire action potentials when a painful stimulus—and that could be like painful heat, a pinprick, pinch—these are all distinguished by different neurons. They transmit that stimulus through the axon. It goes through what's called the sensory ganglion and then winds up in the spinal cord. So, we know that there's one very important population of cells in cancer pain. And when we knock out these cells with a particular plant-derived molecule called resiniferatoxin, or RTX for short, it has a very strong impact on cancer pain and kind of eliminates that. So as a result of that, we're very interested in these cells that make this heat-sensing and inflammation-sensing ion channel called “trip v1” TRPV1 which stands for Transient Receptor Potential Ion Channel V-1.

Iadarola: And what is the V for? The V is for vanilloid. And what does that mean? A vanilloid is—one of the primary vanilloids that almost everybody's familiar with is capsaicin. So that's the active ingredient in hot chili peppers. And in the 90s and 80s, people were very interested in identifying the receptor for capsaicin, which is that active ingredient. They found that, well after many years of trying, the receptor was cloned by David Julius, who in 2021 received the Nobel Prize for cloning the TRPV1 ion channel, but other thermo-sensitive ion channels as well. So, our sensation of the exterior world, whether it be cold, heat, it comes from his work. And he shared the Nobel Prize with a fellow named Ardem Patapoutian, who cloned and identified channels related to touch. So much of what happens on your skin is, and our identification of the molecules that transduce those sensations, comes from the work of Patapoutian and Julius. So, Julius cloned the receptor. We happen to identify this super potent capsaicin molecule called RTX or resiniferatoxin. So that's how we identified these cells. Clearly, we're very interested in those cells and what they make. And the collaboration with Ellen started on that basis. So, what were we interested in Ellen?

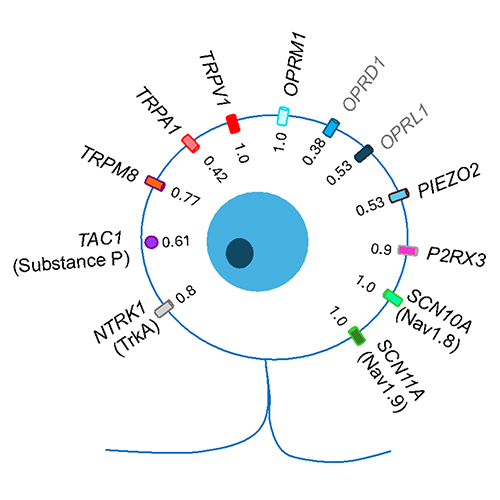

Staedtler: Let me take it from here. So, we also know from clinical experience if we apply an opioid intrathecally, so in the spinal base, that also acts really, is really efficacious to eliminate pain from tissue damage, for example. And we know from the RTX study that where we applied RTX intrathecally that it also attenuates pain very effectively. So, the idea was that it could be the same kind of neurons that are really transmitting this clinically relevant pain. Neurons that express TRPV1, the receptor for RTX, and the opioid receptor, which is the μ opioid receptor, that's the most relevant one. So, we did this in situ two hybridization study looking for expression of these two genes in [dorsal root ganglion] DRG neurons. And we found this population, as we hypothesized it exists. It has these two receptors. And we found this interesting second population. So, we found this dichotomy of DRG neurons. They express both the TRPV1 receptor, one of them expresses the μ opioid receptor, and the other one doesn't.

Markey: Why is this research important?

Iadarola: The importance of Ellen's paper, Ellen and my paper, is that we identify a particular cell, two particular cell populations. So, if you think about how are you going to develop a new drug to treat pain? Well, I could do something in the brain, right? But the brain, if I might say, is a lot of real estate. There's a billion neurons, a bunch of different areas. Which one do I go to? Let's say I want to target a region that neurological disorders, or lesions, would say, well, if this region is damaged with a stroke, then they're indifferent to pain. Well, that's interesting. But how do you operationalize that? Well, difficult, difficult to do it in my opinion. Whereas, if we go at the input function, in other words trying to eliminate signals from reaching the spinal cord, that we can operationalize quite well. However, there's many cells in the sensory ganglion.

Iadarola: We have touch pressure, pinch, cold, heat. Which one do you go to? So, this study shows you directly which one to go to. Actually, it shows you two. If you want to study tissue damage pain, you do TRPV1 μ opiate receptors, and we look at all the genes that are in there. If you want to study neuropathic pain, we look at the ones that are just TRPV1 without the μ, and we look at the genes there. And we try to decipher or find a signpost of which one is the important one to follow.

Markey: Is there an idea or a parting thought you hope listeners take away from this conversation?

Iadarola: Pain is a perception that occurs basically above the neck in your brain. And this perception is distinct from the apparatus that transduce the painful stimuli in the primary afferents, the sensory neurons, that synapse in the spinal cord. So that level that's below the neck and the spinal cord and sensory ganglion is called nociception. We study pain at the nociceptive level. Why study it there? Because if we block pain from entering the nervous system, it's a very effective method for blocking pain. So, anything that prevents these painful, or nociceptive, stimuli from ascending into your brain is a very good way of intercepting things. With RTX, it intercepts the nociceptive signals going from the skin and deep tissue to the spinal cord. It cuts that connection. The significance of these studies is very broad, because, and I'll give you just one example, there's the opiate crisis and everybody's very interested in treating pain obviously, and opiates are very good at treating pain. But they're accompanied by many side effects, such as respiratory depression, which is mainly how you die from an overdose, addiction tolerance, nausea, constipation. And there's been a search for, ever since heroin is introduced like in 1898, for a good pain control agent that's not an opioid.

Staedtler: I agree. I think also like all these molecular techniques that have been developed recently and then apply them in a human, form a really good basis for drug research to find a nonopioid analgesic. The foundation is now laid out slowly and then work can start from there.

Markey: Thank you for listening to Discovering Hope in Science. Stay tuned for our next podcast.

![]() Sign up to receive email updates for NIH Clinical Center Podcast

Sign up to receive email updates for NIH Clinical Center Podcast