Content on this webpage is provided for historical information about the NIH Clinical Center. Content is not updated after the listed publication date and may include information about programs or activities that have since been discontinued.

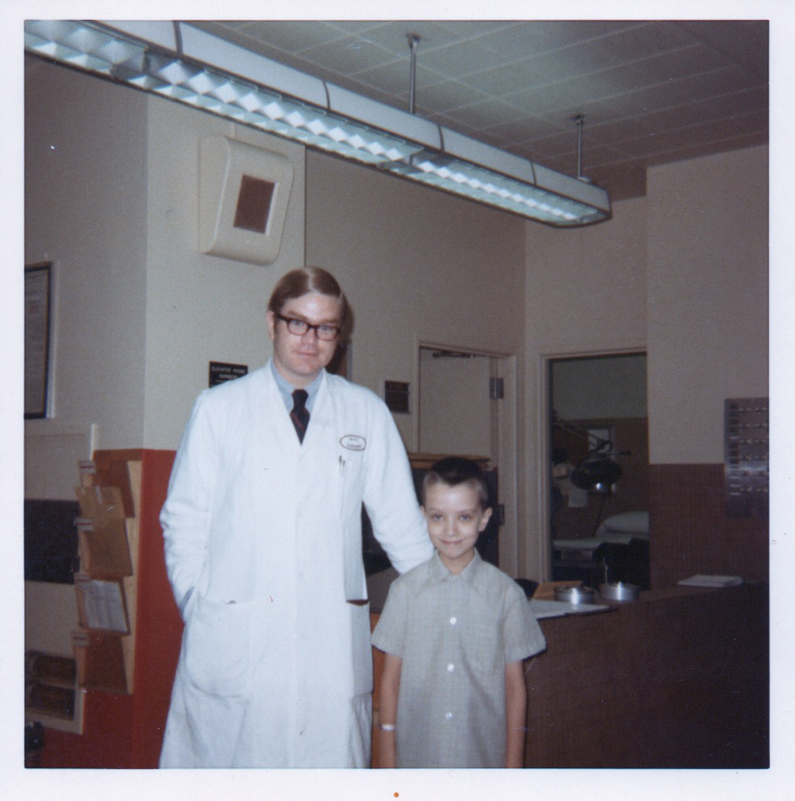

Former Clinical Center patient Tom Kaminski (center) returned "home" to the NIH in June in celebration of his successful open heart surgery five decades ago in Building 10.

Kaminski was born with a tint of blue skin and blue fingernails. Due to a congenital heart defect known as tetralogy of Fallot, it was difficult for blood to flow to his lungs and for his body to get the oxygen he needed.

He couldn't run around with friends in the neighborhood. He couldn't ride a bike. His parents decided to take action. In 1969, they brought him to one of the only places at the time doing heart surgery – the NIH Clinical Center.

"The morning of my surgery Dr. [Andrew] Morrow comes in. I remember him sitting on the end of the bed. He said 'Let me take a listen [to your heart],'" Kaminski recalled. "He takes his stethoscope and says 'It sounds like there's a bee in there. I think we can take care of this. We can either leave it in there and let it be. Or we can take it out and squish it. What do you want me to do?'

"And I said 'Squish it.' Then he proceeded to save my life," Kaminski.

While his parents were on pins and needles about their only child going into surgery for this momentous operation to fix the hole in his heart, Kaminski had only one thing on his mind. Another monumental event in national history.

"I desperately wanted to see the [space] launch,' he said speaking on Apollo 11.

"[The doctors] told me they did delay my surgery until the launch happened," he joked.

"I was in the ICU when the moon landing happened and I have this vague memory of asking my mom 'Did they land on the moon?' I wanted to see that. They wheeled in a television in front of my bed but I couldn't see it because I was surrounded by plastic. At the time that Armstrong gets on the moon, they unzip the thing so I was able to watch it and see that happen. I was released the day [the astronauts] arrived back on earth."

Getting back to his home was a milestone of its own.

"It was like somebody had taken two doors and opened them up and said, 'Okay, there's the world that you were not able to be a part of. Go ahead and be part of that world.' Now I could go play. Ride my bike. It changed everything," Kaminski said.

Kaminski's wife Lyn joked, while flipping through her husband's complete medical record stacked high in front of her, that the best notes in the entire record was that the "effective correction of this child's cardio-malformation shows that he will derive good benefit'.

"50 years later, he certainly did," she said.

View more details of his special day back at the NIH, as well as a deeper-dive into the science that has processed in heart disease research.

- Molly Freimuth