Content on this webpage is provided for historical information about the NIH Clinical Center. Content is not updated after the listed publication date and may include information about programs or activities that have since been discontinued.

Procedure has never been conducted in the Clinical Center before

In August 2018, Trina Davis walked into her first college course at Bowie State University with her mouth shut, elastic bands constricting her ability to communicate. Testimony to her strength and resiliency, Davis was overjoyed to be in class and recovering from a life changing surgery. Ironically, 17-year-old Davis, a senior at Bowie High School, started taking English 101, Public Speaking and Oral Communications just four weeks after orthognathic surgery. The five-hour operation to fix her underbite, caused by underdevelopment of her upper jaw and overdevelopment of her lower jaw, was the first time the procedure was performed in the Clinical Center. While her appearance has changed drastically since surgery – the operation was not for cosmetic purposes. Patients with skeletal underbites (or severe overbites where there is underdevelopment of the lower jaw) deal with headaches, trouble breathing, speech impediments and problems eating and chewing, which can lead to gastrointestinal upset.

"Before surgery, I had trouble chewing certain meats and I had a speech impediment," Davis said. "I had to go to speech therapy to figure out how to form my words correctly. Now, I'm able to better pronounce my words the way I want to. I'm still learning how to chew certain things but I'm getting better. It's getting easier because my bite changed. I feel good that I'm able to contribute to research [and that this] research will help somebody else. I'm appreciative for that."

Davis and her family are part of a natural history protocol led by Dr. Janice Lee, the clinical director at the NIH National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). The study focuses on craniofacial anomalies or developmental growth abnormalities of the head, face and jaw. Lee is on a mission to see if part of the abnormal growth that Davis and others experience has a genetic connection and can be predicted.

"Our genes dictate how we look and those genes run in families. For example, I often hear how a patient recalls having an uncle or grandparent who has the same facial trait, whether it is a large lower jaw or a small nose, etc.," Lee said.

"A well-known example is the 'Habsburg' jaw, a famous European family whose genealogy is linked with the distinct family trait of an underbite," Lee said. "We still don't know exactly which genes cause these features. One of our goals is to see if we can predict who's going to have a certain type of development – specifically abnormal development that causes functional problems."

"When a patient develops abnormally or, for example, the lower jaw grows too far out for too long, it's no longer just an aesthetic concern or dental concern," Lee added. "It's to the point where nothing can be done about it except surgery. Our hope is to identify kids and families at risk for these extreme growth patterns and potentially intervene to avoid surgery. Gene analysis and new imaging technologies have opened up the possibility of predicting these growth patterns."

Just Keep Rowing

Before arriving at the NIH in 2013, Lee had performed hundreds of surgeries to fix a skeletal underbite or overbite and craniofacial birth defects. But Davis's operation would be the first time she conducted it in the Clinical Center. Patient safety was paramount. But to Lee, patient safety comes naturally. In addition to her NIDCR duties, she serves as the chair of the Patient Safety, Clinical Practice & Quality Committee at the NIH. With a few months to prepare, she gathered a multidisciplinary team and got started.

"It took a lot of coordination," Lee said. "I started off by giving a presentation of what I was going to do and examples of the surgery to several groups, including a team of representatives from the Perioperative Medicine Department, Intensive Care Unit, Office of Patient Safety and Clinical Quality, and the unit where Davis would recover. What surgeons have learned is that the more you communicate with everybody who's working with you, the less we will have errors but also just the appreciation of everybody's perspective. Then came the heavy lifting and it could not have been done without Pam Orzechowski, my research nurse, and our craniofacial team. She orchestrated the nursing and support staff."

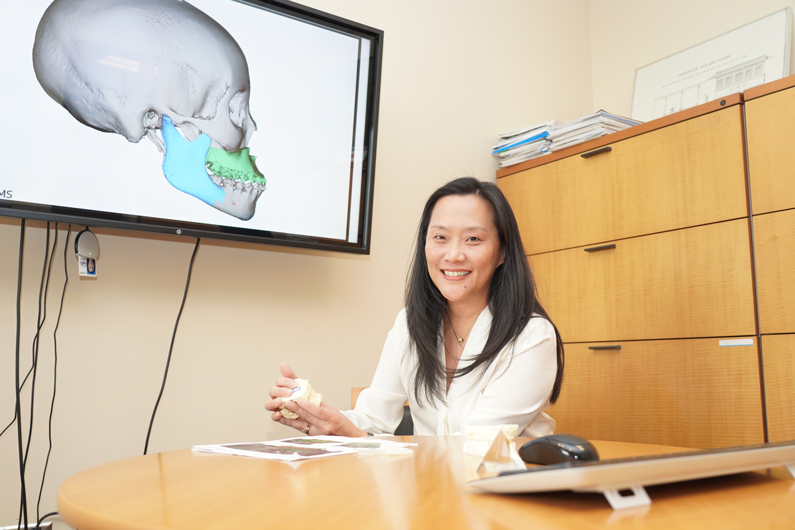

Lee continued training with the operating room team, specialized surgery equipment was gathered from nearby Washington Hospital Center, and the National Naval Medical Center, and surgical checklists were created. As the clinical director, Lee had implemented a proctoring policy for new clinicians, a typical practice in academic medical centers, and chose to apply the policy to herself. Thus, she also brought in Drs. Kal Shastri and George Obeid from Washington Hospital Center to "proctor" her. Dr. James Gilman, the CEO of the Clinical Center, stayed closely attune to the preparation and activities. Virtual surgical planning was initiated about four weeks prior to surgery. With new technologies like 3D cone-beam computed tomography (CT), Lee was able to simulate the surgery on the face, have a surgical guide fabricated and prepare for surgery. These plans were shared with Davis and her parents.

Finally, the day of surgery came.

"I love operating. This hospital is unlike any other," Lee said. "This hospital has been extremely supportive of doing this well and doing this right. The huge trust to do things safely and in a team approach, I think, really resonates with me. When you're in the operating room, you have to work well as a team to be effective. That has really been what I've experienced here. Everybody wants to do what's best for their patients and everybody wants to work together to make it safe."

Lee and her team set forth to fix Davis's jaw. Twenty screws, four plates and several large bone screws were placed. "You don't think about breaks," Lee said. "When you get going, it's like a rhythm. It's like a rowing team. You just start moving down the river and lo and behold you cross that finish line. As a senior surgeon, one of the things I really work to refine is the economy of motion – meaning every move, every effort has to matter and has to be efficient. We trim off minutes here, minutes there which becomes hours and then the patient no longer requires six hours of anesthesia, its five hours or less."

"I've built surgical teams [before coming to NIH and] it took years to get everybody to work smoothly," Lee added. "Here, I don't know what it was. Maybe the laser focus everybody brought. Maybe the fact that everybody was super engaged. It [was] remarkably smooth."

More Than a Guess

Lee's goal is to enroll 1,500 patient partners and healthy volunteers over the course of 20 years to start looking at the genetic etiology and to see if she can predict these conditions.

"People often ask me when they bring in their first child, 'Is this going to happen to my second, or third, or fourth child?' and I've never been able to give them a good answer," Lee said. "The best answer is 'Let me look at mom and dad. Let me get an idea.' But it's a guess."

Through the course of the research, "if it turns out to be very difficult [to identify] mutations or variants, we will work on predictive tools using computational methods and high-resolution/low-radiation cone-beam CT scan," Lee said. "We need a multi-pronged approach because in medicine it is rarely a one answer for every patient."

Two-dimensional x-rays are a thing of the past. Lee is excited to see how three dimensional cone-beam CT scans can bring high resolution, low radiation, better surgical simulations and prediction capabilities in the years to come. With this technology, "We get to see if there are certain things about the shape of the skull base and the rest of the face that would give us some ideas that somebody will grow differently. When they're born, it's not obvious. When they hit puberty, for some reason, the lower jaw may continue to grow."

Pamela Orzechowski, Lee's research nurse coordinator, said "Perhaps we can eventually provide some early intervention or stop the overgrowth of the jaw so a patient will not have to undergo surgery."

In January 2019, Davis returned for a check-up. With a smile on her face, and all A's on first semester of college courses, she said "once you start seeing actual results in your face as the swelling goes down, you know it was worth it. You see how things have changed for the better."